THE FAR-RIGHT POLITICAL PARTIES OF

THE EUROPEAN UNION IN THE CONTEXTS OF IMMIGRATION AND TERRORISM

Sage McCarty

Political Science 201: Political

Research Design

May 21, 2023

Link to Poster (Opens in New Tab)

Sections

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Methodology

- Data Analysis and Findings

- Conclusions

- Bibliography

Abstract

Rhetoric on behalf of the far-right

linking immigration and terrorism provides an opportunity to analyze whether

instances of terrorist attacks or high levels of immigration, or both

phenomena, can be used as predictors for electoral support for the far-right. Correlations and linear relationships between

general variables of immigration and terrorism do not necessarily support

far-right rhetoric, as anti-immigrant rhetoric regarding terrorism may center

on certain demographic factors, such as the religion of perpetrators of

terrorist attacks

Immigration levels and far-right

success are simultaneously rising among European Union member countries during

a period in Europe marked by concerns over changing demographics and threats of

terrorism. This establishes a context

where possible relationships between far-right success, immigration levels, and

terrorism should receive attention. However,

analyses using correlations and linear regression reveal that a European Union

member country’s number of terrorist attacks, number of terrorism-related

arrests, and number of incoming migrants each year are not suitable predictors

for the percentage of the vote in a country that is cast for the far-right in

European Parliament elections during the following year.

Introduction

The far-right in Europe is gaining increasing success

in elections for the European Parliament in a period where the level of

immigration to European Union member countries, as an independent variable, consistently

has a significant, moderate, and positive linear relationship with the number

of terrorist attacks in those countries; despite this context, the success of

far-right parties in countries’ elections to for the European Parliament is not

adequately predicted through the use of independent variables pertaining to

immigration and terrorism. The first

section of this research paper, the literature review, explores existing

literature on voter behavior, the far-right, migration, and terrorism,

particularly as they pertain to European politics, for example, by providing

existing explanations for far-right electoral successes. The second section of this paper describes

the methodology used throughout the research process, whether related to

operational definitions of certain variables, the use of a translation tool to

overcome language barriers, the collection of data, statistical analysis, or

the establishment of what European parties are properly categorized as

far-right. The third section on data

analysis and findings explains statistical analyses on immigration, terrorism,

and far-right successes, along with the relationships of these phenomena with

each other; this section includes five parts that cover the topics of trends

regarding terrorism and immigration separately, potential relationships between

far-right successes and terrorism, potential relationships between far-right

successes and immigration, potential relationships between terrorism and

immigration, and the increase over time in the number of countries in the

European Union that had a far-right party win a notable percentage of the vote

in elections for the European Parliament.

The concluding section summarizes earlier findings, provides

recommendations for future research, and clarifies and expands on this

project’s findings.

Literature Review

The overall rise of the far-right in Europe, along with

relationships between elections, migration, terrorism, and other phenomena, have

received recent attention in political science literature and literature

surpassing disciplinary barriers. For

example, Larisa Doroshenko from the University of

Wisconsin—Madison analyzed ten European Union countries and their European

Parliament election results to conclude that consumption of “mass-market news

sources” increased voters’ tendencies to support far-right parties (2017, 3186,

3199). For example, voters were more

likely to support the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) after using news

sources on the internet (3200). Cas Mudde from the University of Georgia and the University of

Oslo writes that far-right populist ideas entered mainstream politics in Europe,

to the point where even “[m]ainstream parties” openly

describe “immigration and multiculturalism as threats,” due to the recent

influx of refugees into the continent; this marked the end of the far-right’s

position on the fringes of European politics (2019, 32-33). Furthermore, Mudde

points out Hungary’s ruling Fidesz party as a conservative

party affected by the integration of far-right ideas into mainstream politics

(33). The findings of Doroshenko and Mudde represent

the potential for multiple factors—in these cases, the factors of changes in

communications and immigration—impact the success of far-right parties in

Europe. A study on the cultural and

economic variables contributing to far-right success in Europe also found that

poor economic conditions have a positive correlation with far-right success;

this study hypothesizes that far-right support may arise among “more affluent

regions” due to these poor economic conditions, while the far-right “subgroups”

of the “extremist right” and the “populist radical right” do not capitalize on

these conditions for the sake of their own political promotion to a great

extent (Georgiadou, Rori,

and Roumanias 2018, 103, 113). These subgroups have a further

differentiation between the extremist right and the populist radical right,

with the extremist right receiving more support in the face of poor economic

conditions, while the populist radical right receives more support in light of “cultural threats” tied to immigration (113). Therefore, the literature attests to

far-right successes having positive relationships with poor economic

conditions, immigration, and methods of communication.

Existing literature contains studies

focused on specific countries as well as studies spanning across continents that

analyze relationships between voter behavior, terrorism, and migration. A study by Marc Helbling

and Daniel Meierrieks involving multiple countries

across different continent states that immigration does not “unconditionally”

contribute to an increased number of instances of terrorism, while terrorism contributes

to views and legislation against immigration (2020, 977-978, 981). This study also establishes a connection

between terrorism and far-right electoral success by affirming “that terrorism…

benefits (right-wing) political parties that hold nativist views” (992). Meanwhile, a paper focused on Spanish

elections and terrorist attacks perpetrated by the Basque organization Euskadi Ta

Askatasuna (ETA) found that people are more inclined

to be involved in democratic processes after terrorist attacks, with attacks

against civilians influencing voter behavior this way more so than attacks

against military or law enforcement officers; as stated in the article, this

behavior echoes a theory that the feeling of anxiousness resulting from

terrorist attacks motivates involvement in politics. However, the study does not express that this

feeling of anxiousness contributes to a tendency to vote for parties with

certain ideological leanings, and the study instead affirms that terrorism does

not impact the voters’ support for parties that are already in office

Studies surrounding immigration’s

relationship to far-right electoral successes are mixed. A study focused on Finland found a negative relationship

between immigration and support for far-right parties, where increased

immigration negatively impacts the percentage of the vote in local elections

that goes to the Finns Party, a far-right party, “by 3.4 percentage points”

with every “1 percentage point increase in the share of foreign citizens in a

municipality;” instead, “1 percentage point” increases in immigrant populations

actually result in a shift of these “3.4 percentage points” to political parties

that favor immigration. Immigration also

contributes to an increased tendency to vote among people who support

immigration

Methodology

This project uses linear regression

to discover relationships between immigration, terrorism, and the success of

far-right parties in European Parliament elections. Variables derived from these concepts are

defined in line with the origins of the data.

For example, far-right success, a product of voter behavior, is defined

as the percentage of the vote in a country that was cast for a far-right party

(or far-right parties) in a given country in its election for the European

Parliament in a given year; the data for this variable is derived from the

European Parliament’s electoral returns

While working in the realm of

causation, data from the previous year are used to potentially explain data

from the following year; for example, data from 2018 regarding immigration and

terrorism are used to explain the percentage of the vote won by far-right

parties in countries in 2019.

Furthermore, data on far-right success, terrorist attacks, and

terrorism-related arrests were gathered manually. For instance, TE-SAT reports were used for

data on the number of terrorist attacks and arrests connected to terrorism in a

given EU country in a given year, and United Kingdom

figures are missing for the years 2020 through 2021 as a result of the United

Kingdom’s exit from the European Union (“Brexit”). Brexit likewise resulted in an absence of

immigration data for the United Kingdom in 2020 and 2021. Croatia is similarly also missing data

regarding immigration from 2010-2011 and terrorism in 2012. Data was not used from other sources for the purpose

of generating a normalized data set; other data sets may define immigration and

terrorist attacks differently—for example, through having different answers to

questions of whether migration between countries within the EU counts as

immigration, or whether a definition of a terrorist attack includes actions

that were prevented by law enforcement agencies—so only TE-SAT reports on

terrorism and Eurostat immigration were used.

Missing data were manually marked within Microsoft Excel files with

“-999.”

Furthermore, results from the

European Parliament’s elections were used due to the efficient and structured

natures of the frequency of elections (every five years) and simultaneous

elections within every EU member country.

Parties who supported candidates within these elections were defined as

far-right based variously on journal articles, news articles, and information

from websites. PolitPro,

an election information resource, was especially helpful in determining what

parties to consider as having a far-right position and in deciding what parties

to investigate for far-right tendencies

Data points were collected using

Microsoft Excel and analyzed using JASP, a statistical analysis tool. Classical correlation and linear regression

were primarily used to explore relationships between multiple variables, with

these relationships calculated through JASP.

Variations and averages within a single data set—such as within the

category of immigration—were calculated using Microsoft Excel and Google

Sheets.

Data Analysis and Findings

Part 1: Trends in Immigration and

Terrorism

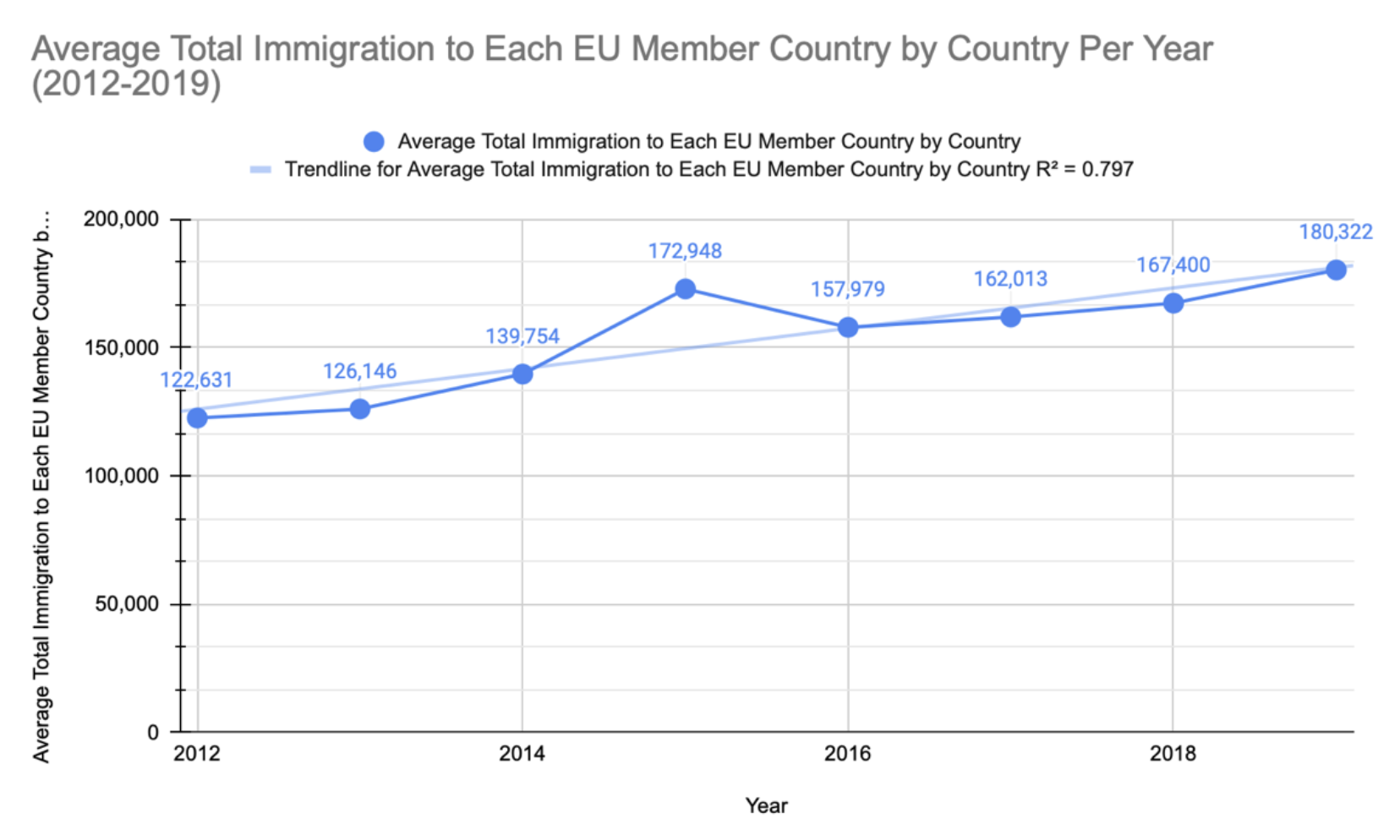

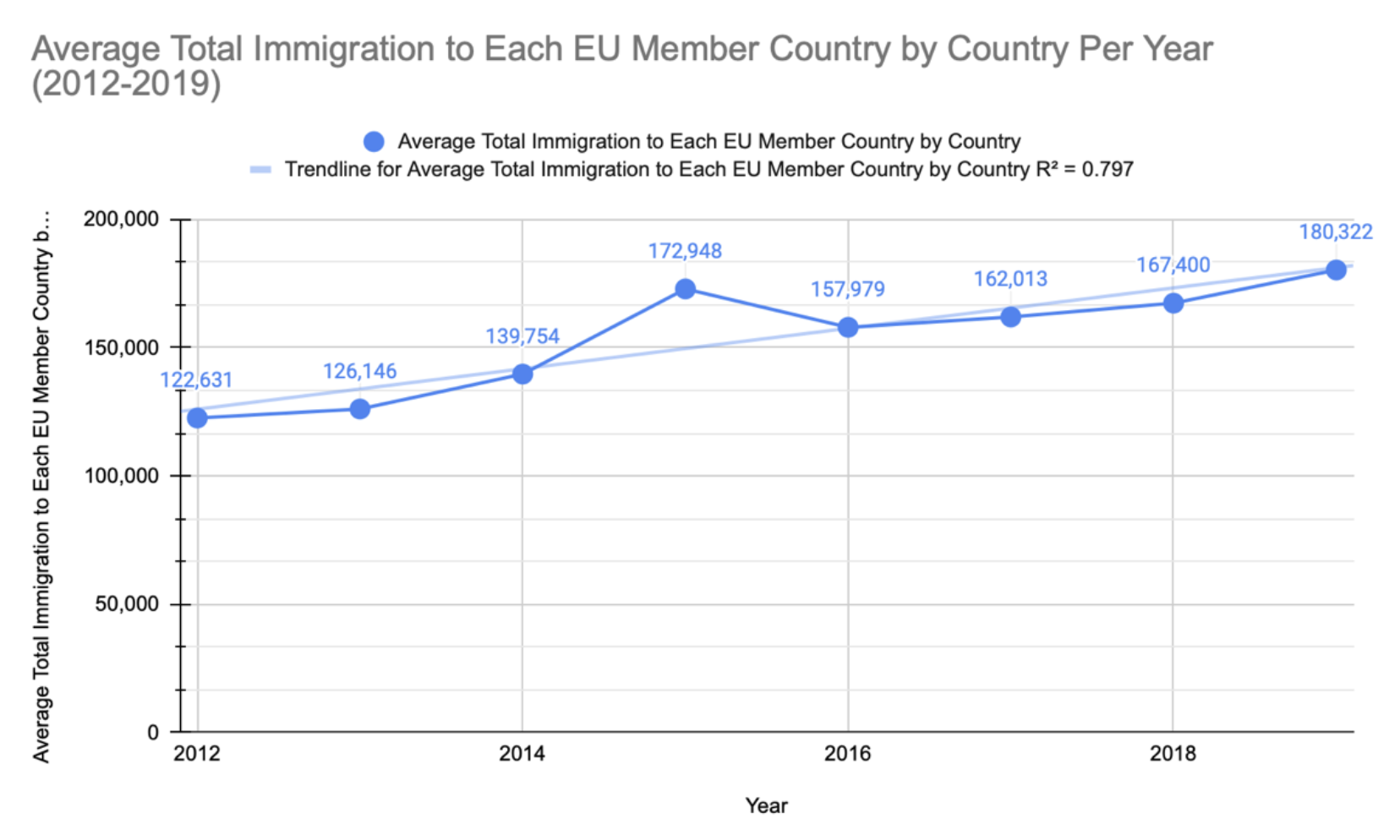

As calculated through Microsoft

Excel, Eurostat migration data indicates a steady increase in immigration to EU

member countries from 2012 to 2019; the years 2010, 2011, 2020, and 2021 were

excluded from this analysis, despite the availability of data regarding these

years, to account for missing data for immigration to Croatia in 2010-2011 and

the United Kingdom from 2020-2021.

Despite this steady increase, there is a spike in 2015 with an average

of 172,948 migrants arriving in each EU member country. This spike may be linked to the Syrian

refugee crisis that began in 2014. After

this spike, the average level of immigration resumes to its general rise along

its trendline, as displayed through Google Sheets (shown below in Chart 4.1.1). There is a strong, positive, and linear

relationship between the year of immigration and the average total immigration

to each EU member country, as indicated by the regression coefficient (R2

value) of 0.797. Therefore, the average

level of immigration to European Union member countries steadily increased in a

strongly linear manner from 2012 to 2019.

Chart

4.1.1: Changes in average migration level to each EU member country per year,

2012-2019.

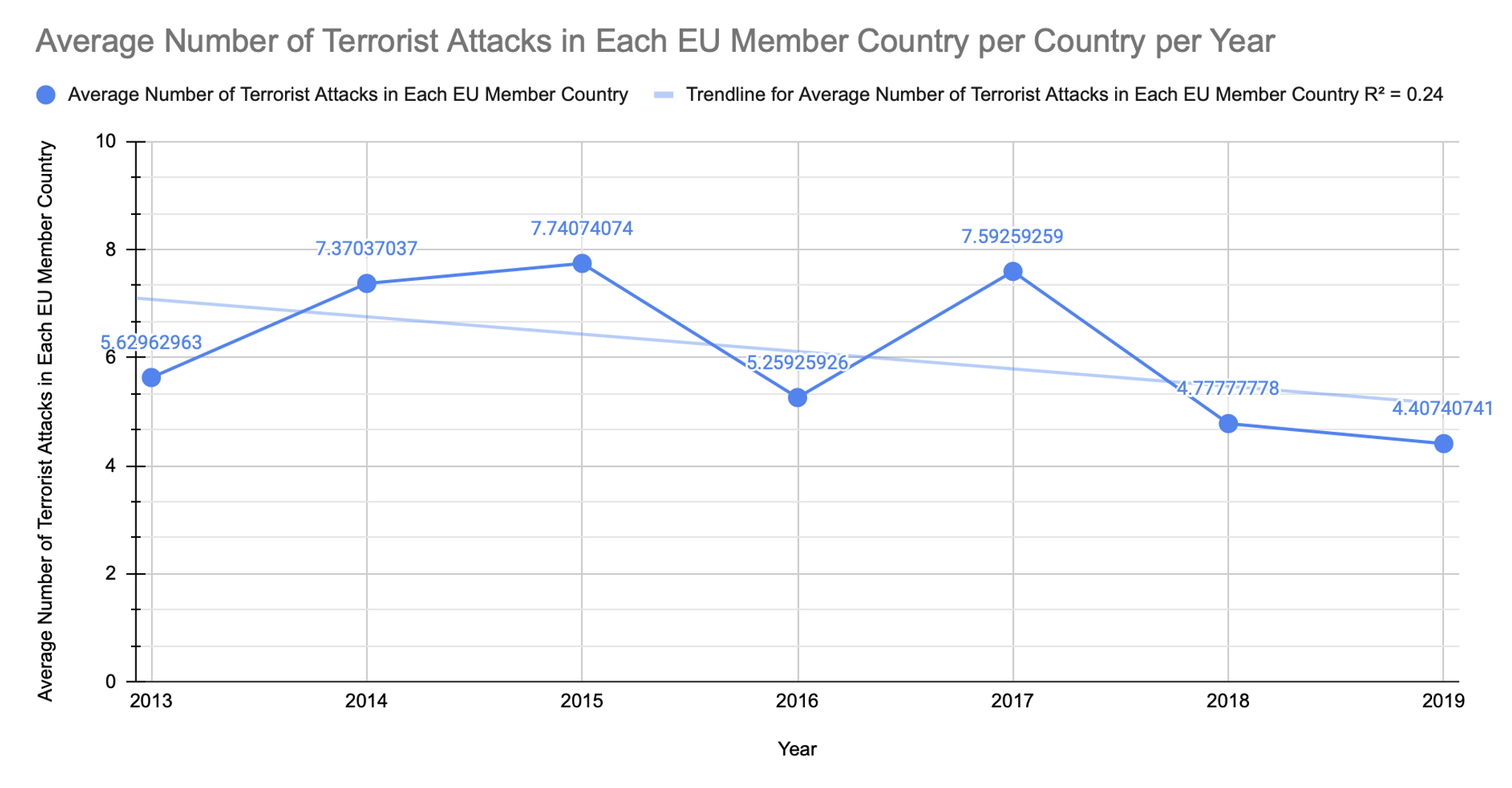

Furthermore, a longitudinal approach

to studying changes in the numbers of terrorist attacks each year reveals that,

in the years 2013 through 2019, there is only a weak, negative, and linear

relationship between the year and the number of terrorist attacks in each EU

member country, as indicated by the low regression coefficient (R2

value) of -0.24. This weak, negative,

and linear relationship indicates that, although the average number of

terrorist attacks in each European Union country tends to decline each year, the

decline in the average number of terrorist attacks per year in each European

Union member country is not consistent.

Also, the weakness of this relationship (R2 = -0.24) stands

out against the strength of the relationship between the year and the average

level of immigration to each European Union member country per year (R2

= 0.797). Immigration levels to each

European Union member country increase more consistently per year than the

average number of terrorist attacks in each member country. The below graph (Chart 4.1.2) utilizes TE-SAT

report data and excludes years prior to 2013 and after 2019 to account for the

lack of Croatian and United Kingdom data during those periods, respectively. Also, there are no clear spikes in the data

due to the linear relationship being weak.

Chart

4.1.2: Changes in average number of terrorist attacks in each EU member country

per year, 2012-2019.

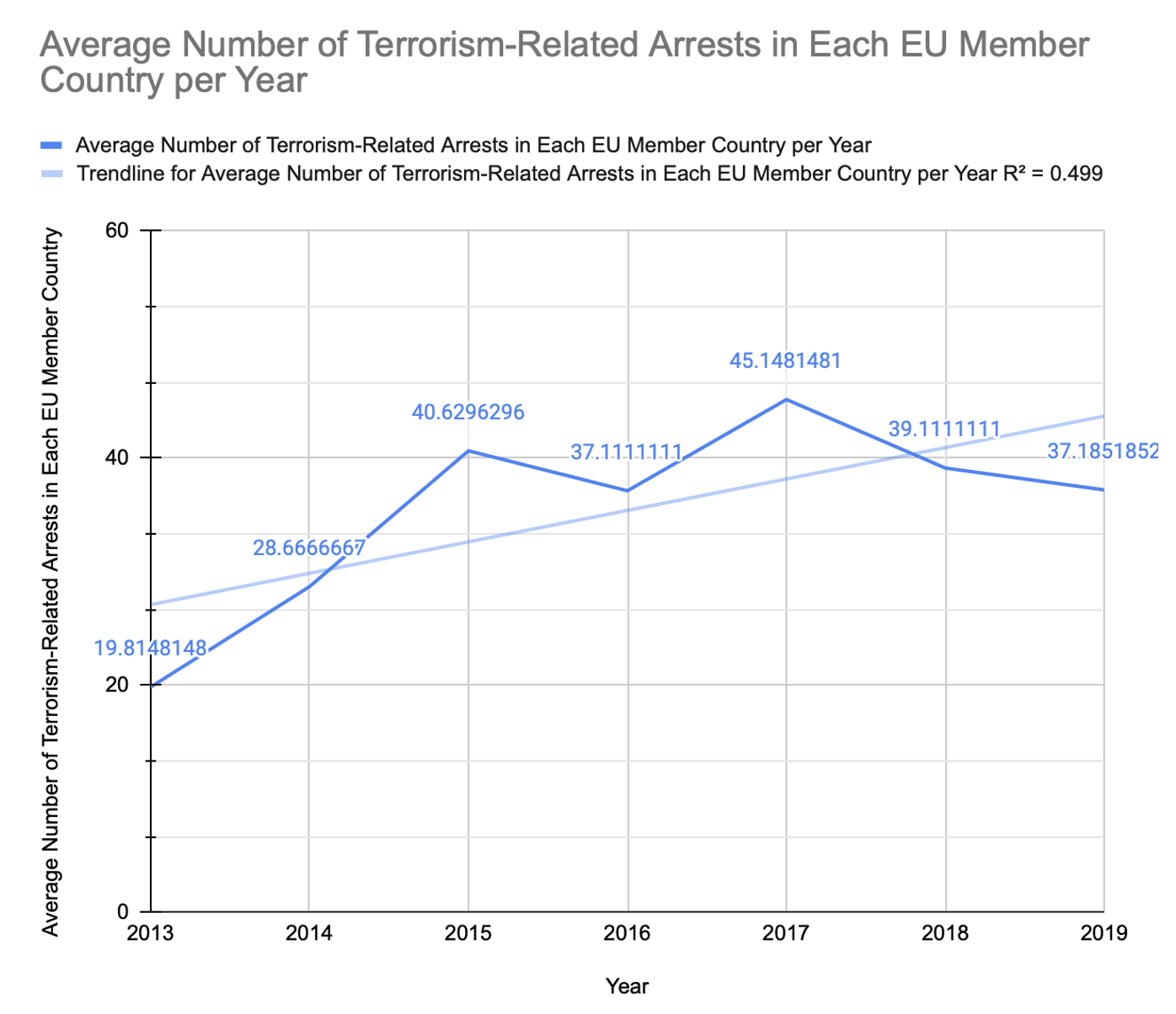

In the years 2013 through 2019,

there is a moderate, positive, linear relationship between the number of

terrorism-related arrests in each EU member country per year and the year of

the arrests, as indicated by the regression coefficient (R2 value)

of 0.499. This regression coefficient

indicates that the increase in the number of terrorism-related arrests in each

European Union member country per year is somewhat consistent. Similar to the above

data on terrorist attacks, the moderate relationship leads to the absence of

clear spikes in the data. The below

graph (Chart 4.1.3) shows the change in the average number of terrorist attacks

in each EU member country per year from 2013 to 2019.

Chart

4.1.3: Changes in average number of terrorism-related arrests in each EU member

country per year, 2012-2019.

Therefore, the rate of the increase

in average immigration levels (R2 = 0.797) is higher than the rate

of the increase in the average number of terrorism-related arrests (R2

= 0.499) among EU member countries from 2013 to 2019. Although the average number of

terrorism-related arrests is steadily rising during these years, the average

number of terrorist attacks in EU member countries is inconsistently declining

(R2 = -0.24); however, the relationship between the year of the

attacks and the average number of terrorist attacks in EU member countries is

weak due to the low regression coefficient.

Part 2: Far-Right Success and

Terrorism

First

Model: Far-Right Successes in 2014 and Terrorism in 2013

Far-right successes in the European

Parliament’s elections are not adequately explained by data related to

immigration or terrorism; essentially, a country having a high level of

immigration or a high number of terrorist attacks in a year preceding elections

for the European Parliament do not strongly or significantly correlate, or have

a linear relationship, with a high percentage of the vote in those countries

going to a far-right party (or parties) in the next year’s elections for the

European Parliament. First examining

possible relationships between immigration in 2013 and far-right success in 2014

supports this conclusion, as there is only a weak correlation (Pearson’s r =

0.206) that is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.304) between these

variables. Regarding a linear

relationship between these two variables as calculated through linear

regression, with far-right success as the dependent variable and terrorist

attacks as the independent variable, there is a weak relationship (standardized

regression coefficient = 0.206) that is not statistically significant (p-value

= 0.304) between these two variables.

The weakness of the correlation and the linear relationship indicate

that the success of the far-right of different European Union member countries

in 2014 was only inconsistently related to high numbers of terrorist attacks in

the countries in 2013.

The R2 value for this

model is 0.042, and it only slightly improves to 0.043 when incorporating the

number of terrorism-related arrests in a country in 2013 into this model as an

independent variable; the low degree of improvement to this model may be caused

by the independent variable of the number of terrorism-related arrests in a

country in 2013, when used alone, only having a weak positive, and linear

relationship (standardized regression coefficient = 0.188) that is

insignificant (p-value = 0.439) with the percentage of the vote that was cast

for the far-right in a country in the 2014.

Even when used together, neither the number of terrorist attacks in a

country in 2013 nor the number of terrorism-related arrests in a country in

2013 are suitable predictors for the percentage of the vote that was cast in

that country that went to a far-right party (or parties) in the 2014 elections

for the European Parliament.

Second

Model: Far-Right Successes in 2019 and Terrorism in 2018

This pattern continues when

analyzing the next election for the European Parliament in 2019. There is only a weak correlation (Pearson’s r

= 0.182) between the number of terrorist attacks in each EU member country in

2018 and the percentage of the vote won by far-right parties in the 2019

elections for the European Parliament, and the relationship between these

variables is not significant (p-value = 0.364).

The linear relationship between these two variables, with far-right

success as the independent variable and terrorist attacks as the independent

variable, is positive and weak (standardized regression coefficient = 0.182). Also, this linear relationship is not

statistically significant (p-value = 0.364).

The weakness of both the

correlation and the linear relationship means that the success of countries’

far-right parties in 2014 was only inconsistently related to high numbers of

terrorist attacks in a country in 2013.

Incorporating the independent

variable of the number of terrorism-related arrests in each country in 2013

into this model only slightly improves the model’s R2 value from 0.053

to 0.054; this low degree of improvement may be caused by the presence of only

a weak positive and linear relationship (standardized regression coefficient =

0.182) that is insignificant (p-value = 0.364) between the dependent variable

of far-right success and the independent variable, when used alone, of the

number of terrorism-related arrests in a country. Therefore, reflecting the results of the

previous model on terrorism and voter behavior, neither the number of terrorist

attacks in a country in 2018, nor the number of terrorism-related arrests in a

country in 2018, are suitable predictors for the percentage of the vote in a

country that was cast for a far-right party (or parties) in the 2019 elections

for the European Parliament, even when these independent variables are used simultaneously

in the same model.

Findings

on Far-Right Success and Terrorism

Both the first and second model reveal

that neither the number of terrorist attacks in a European Union member country,

nor the number of terrorism-related arrests in the country, are appropriate

predictors for the percentage of the vote in a country that will be cast for the

far-right in the next year’s European Union elections, even when these

variables are used in combination. The

insignificance of the correlational and linear relationships involving the

variables on terrorism and far-right success indicate that observations of

correlational and linear relationships are properly explained by random chance. It is possible that the mistake of a Type II

error was made during the related calculations and analysis, meaning that,

although the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between terrorism

and far-right success was not rejected, this null hypothesis should actually have been rejected.

If this error was committed, the alternative hypothesis that there is a

positive linear relationship between terrorism and far-right success should

have received support in accordance with evidence in favor of this

hypothesis. Fixing this error would

require increasing the project’s sample size; however, the inclusion of only

European Union member countries through the focus on the European Parliament

prevents the expansion of the sample size to include more countries. The construction of models with future data,

or data from before 2013, may reveal a correlation or linear relationship

between terrorism and far-right success that is not present in these two

models. Based on these two models, the

numbers of terrorist attacks in European Union member countries and the numbers

of terrorism-related arrests in these countries are not accurate predictors for

the percentage of the vote that went to the far-right parties of these

countries during the following years’ elections for the European Parliament.

Part 3: Far-Right Success and

Immigration

First

Model: Far-Right Success in 2014 and Immigration in 2013

Regarding the relationship between the

percentage of the vote that was cast for the far-right in a country in 2014 and

the number of migrants entering a country in 2013, with far-right success as

the dependent variable and the level of immigration as the independent variable,

there is a moderately weak, positive, and linear relationship (standardized

regression coefficient = 0.346) that is not statistically significant (p-value

= 0.077) between these two variables. Similarly,

the correlation between far-right success in 2014 and immigration in 2013 is not

statistically significant (p-value = 0.077), and the correlation is positive

and moderately weak (Pearson’s r = 0.346).

The weakness of the correlation between these two variables and the weakness

of their positive linear relationship indicate that far-right success does not consistently

increase in accordance with increases in immigration. Due to the high p-values regarding

correlational and linear relationships, random chance adequately explains the

observations, and the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between

immigration in 2013 and far-right success in the election for the European

Parliament in 2014 should not be rejected.

Considering the high p-value of 0.077, the data does not support the

alternative hypothesis that the percentage of the vote won by the far-right of

different countries in 2013 is explained by the countries’ levels of immigration

in 2014.

Second

Model: Far-Right Success in 2019 and Immigration in 2018

A similar positive, moderately weak,

and linear relationship without statistical significance also exists in an

analysis of a possible relationship between different European Union countries’

levels of immigration in 2018 and the electoral success of the far-right in different

countries’ elections for the European Parliament in 2019. This relationship has a p-value of 0.305 and

a standardized regression coefficient of 0.205, with immigration as the

independent variable and far-right success as the dependent variable. The correlation between these two variables

has a correlation coefficient, or a Pearson’s r value, of 0.205 and a p-value

of 0.305. The weakness of the positive

correlational and linear relationships indicate that the

success of the far-right parties of different countries in European Parliament

elections in 2019 is only inconsistently related to a high level of immigration

into these countries in 2018.

Furthermore, the high p-values show that observations of these

correlational and linear relationships have a high likelihood of resulting from

random chance. Therefore, the level of

immigration to a European Union member country in 2018 is not an adequate predictor

for the percentage of the vote in that country that went to the far-right in

the country’s 2019 elections for the European Parliament.

Findings

on Far-Right Success and Immigration

Among the two relevant models that

were constructed, there is a moderately weak, positive, and linear relationship

between the level of immigration during a certain year and the percentage of

the vote in a country that was cast for the far-right in the election for the

European Parliament the next year.

However, this relationship is not statistically significant, so the

success of the far-right parties of certain countries in elections for the

European Parliament is not adequately explained by the previous year’s level of

immigration in those countries; instead, random chance properly explains the

observations of moderately weak, positive, and linear relationships within

these models. Analyses of correlations

between the same variables used in these models likewise reveals only

moderately weak and positive relationships.

The weakness of the correlational and linear relationships that were

analyzed in connection with these models reveals that the levels of immigration

to European Union member countries are only inconsistently related to the

success of these countries’ far-right parties in elections for the European

Parliament in the following years.

Although the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between

levels of immigration and the success of far-right parties should not be

rejected, a Type II error could have been committed. In this situation, this type of error means

that the null hypothesis should have been rejected and that evidence should

have been found that supports the alternative hypothesis that there are

positive correlational and linear relationships between the success of countries’

far-right parties in elections for the European Parliament, as the dependent

variable in the setting of linear regression, and the countries’ levels of

immigration during the following year, as the independent variable used in

linear regression. Fixing this error

would require increasing the project’s sample size; this is not possible given the

project’s current focus on countries the European Parliament, as an increase in

sample size would most likely include countries that are not members of the

European Union. The current focus on

connections between immigration and far-right success in elections for the

European Parliament reveals that a country’s level of immigration in one year is

not a suitable predictor for the percentage of the vote cast in that country

that went to the far-right in the election for the European Parliament in the

following year.

Part 4: Terrorism and Immigration

There is consistently a moderate,

positive, and linear relationship between the level of immigration to an EU

member country (independent variable) and the number of terrorist attacks in an

EU member country the following year (dependent variable), with the

standardized regression coefficients ranging between 0.393 in 2016 and 0.581in

2014 between 2012 and 2021 (Chart 4.4.1).

Although earlier calculations indicate that the average number of

terrorist attacks in each EU country decreased per year between 2013 and 2019,

while the average level of immigration to each EU country increased per year

between 2012 and 2019, there is still a moderate, positive, and linear

relationship—with a standardized regression coefficient ranging from 0.393 to

0.581—between the level of immigration during the previous year and the number

of terrorist attacks in EU member countries between 2012 and 2021. Also, out of the ten models generated for

this relationship to cover the years of terrorist attacks ranging from 2012 to

2021, all of the models show linear relationships that

are statistically significant when using a significance level of 0.05. This means that, by random chance, there is

less than a 5% chance of observing a moderate, positive, and linear

relationship between the level of immigration the previous year in an EU member

country (independent variable) and the number of terrorist attacks in an EU

member country between the years 2012 and 2021 (dependent variable), with these

relationships having standardized regression coefficients between 0.393 and

0.581. Due to these consistently low

p-values and the consistent appearance of moderate, positive, and linear

relationships, the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between

terrorism and immigration is rejected; instead, there is have evidence that

supports the alternative hypothesis that there is a positive, moderate, and

linear relationship between the number of terrorist attacks in an EU member

country and the level of immigration to that EU member country during the

previous year.

Chart

4.4.1: Changes in correlation coefficient for linear relationships between the

level of immigration to an EU member country in the previous year (independent

variable) and the number of terrorist attacks in that country during a

particular year (dependent variable), 2012-2021.

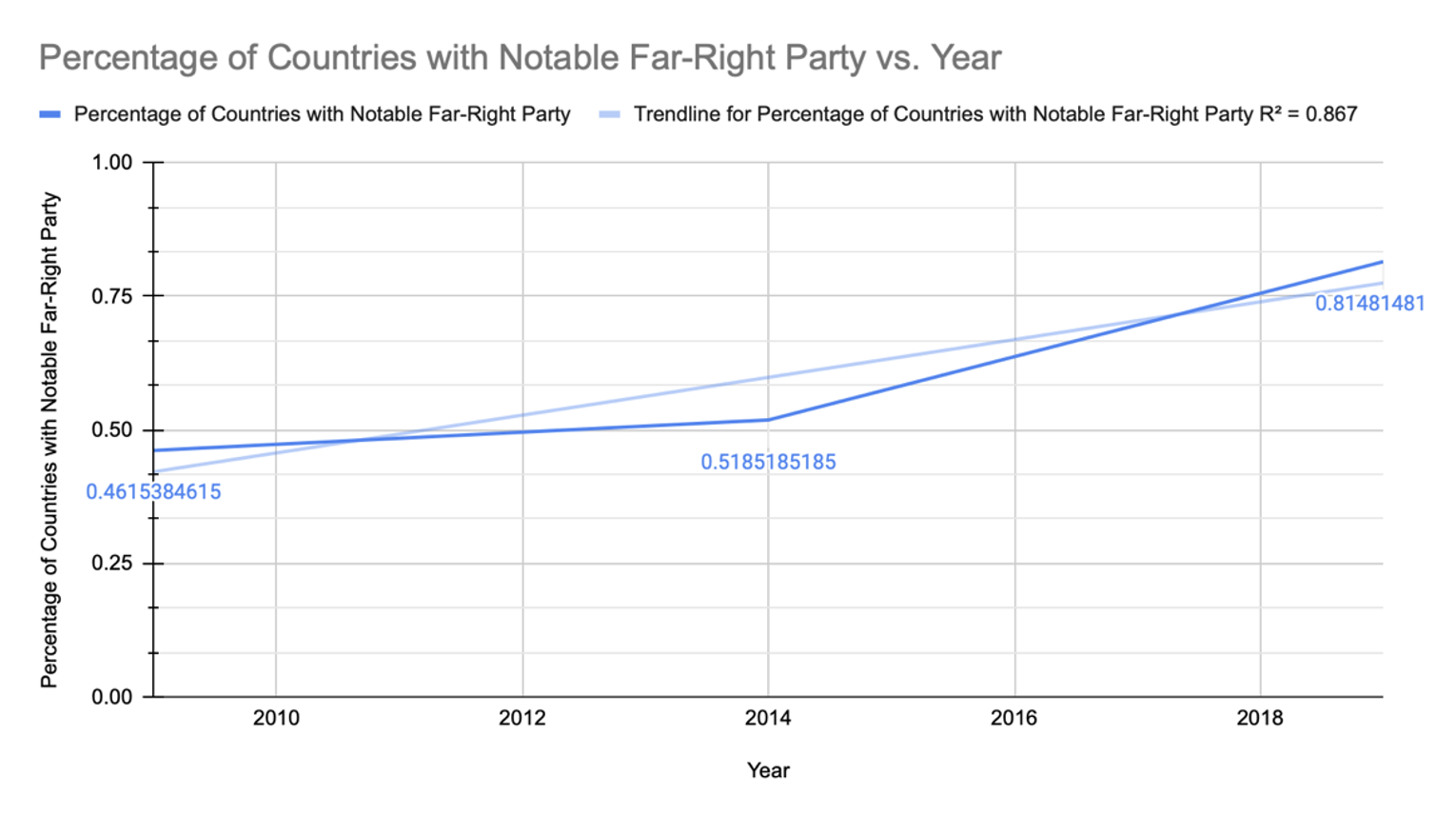

Part 5: Far-Right Parties Achieving

Notable Status

The percentage of European countries

who have a notable far-right party in regard to

European Parliamentary elections has gradually increased since 2009. Here, the idea of notable far-right parties

refers to far-right parties who received a percentage of the overall vote in

their country high enough for the percentage of the vote won by them to be

displayed on the European Parliament’s electoral return website, rather than

there being no far-right party involved in the election or the far-right party

(or parties) receiving a percentage of the vote in their country that was so

small that the result is relegated to the combined “Other parties” section in

the election results

Chart

4.5.1: Changes in the percentage of countries who had at least one far-right

party win a notable percentage of the country’s vote in the elections for the

European Parliament over the years 2009, 2014, and 2019.

Conclusions

While there is a moderate and significant linear

relationship between terrorism and immigration, there is no such relationship

between terrorism and far-right success or immigration and far-right success. The lack of significance among correlational

and linear relationships between terrorism and far-right success, along with

those between immigration and far-right success, demonstrates that variables

related to immigration and terrorism are not suitable predictors for the

percentage of the vote cast for the far-right in a country’s elections for the

European Parliament; this conclusion is further supported by how the weakness

of these correlational and linear relationships shows that variables related to

immigration and terrorism are only inconsistently connected to far-right

success in elections for the European Parliament. These conclusions indicate a possibility that

support for far-right parties in European Parliamentary elections may not

result from voters’ fears regarding multiculturalism or personal security. Furthermore, the relationship between

terrorism and immigration does not account for attributes such as the

perpetrators’ countries of origin or motives; it is inappropriate to state,

based on the linear relationship, that immigration leads to terrorism through

immigrants committing acts of terrorism.

Instead, acts of terrorism may be committed, especially by far-right

perpetrators, out of fears related to immigration.

Far-right sentiment is increasing

within Europe, as attested by the literature regarding this subject and by my

above finding on the gradual increase of the percentage of EU countries that

had a far-right party achieve a notable percentage of the vote in European

Parliamentary elections. While

immigration, terrorism, and far-right successes are simultaneously realities

for the European Union, the lack of consistency in associations between

immigration and far-right successes and between terrorism and far-right

successes leads to the conclusion that it is inappropriate to consider far-right

successes as byproducts of trends related to immigration and terrorism.

Further research should grant

attention to finding variables that contribute to increased electoral success

among the European Union’s far-right parties while using a wider range of tools

for statistical analysis. While this

project used correlations and linear regression to explore relationships

between variables, future research would benefit from the use of more diverse

methods of finding relationships between far-right success and its potential

predictors. Furthermore, future research

on connections between terrorism and voter behavior would benefit from an

exploration of how the scope and publicity of terrorist attacks impact voter

behavior; data used in this project does not allow for the number of people affected

by certain terrorist attacks or the scope of knowledge about certain attacks to

be factored into analyses on terrorism and far-right electoral successes. Also, although the recent success of

far-right parties in elections for the European Parliament may not receive

adequate explanation through variables centered on terrorism and immigration, the

inadequacy of these variables provides the insight that voters may support

far-right parties out of concerns related to other matters, such as economic

troubles or Euroscepticism, or that voters may be influenced to support

far-right parties based on more specific concepts that fall under terrorism and

immigration, such as the ideological motives for a majority of terrorist

attacks or the countries of origin of a majority of immigrants. Thus, the insight gained from these analyses on

the inadequacy of variables related to immigration and terrorism for explaining

far-right electoral successes has the potential to guide the focus of future

investigations into reasonings for the electoral successes of the European

Union’s far-right parties.

Bibliography

2019.

2019 European election results. European Parliament. October 23.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en.

Alan-Lee, Nathan. 2023. Poland’s Far-Right Advances on

Anti-Ukraine Sentiment. Center for European Policy Analysis. April 13.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://cepa.org/article/polands-far-right-advances-on-anti-ukraine-sentiment/.

2013. All about the Alternativ Demokratësch Reformpartei

(ADR). Mediahuis Luxembourg S.A. June 10. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.luxtimes.lu/en/luxembourg/all-about-the-alternativ-demokratesch-reformpartei-adr-602d460dde135b9236510185.

2017. Anatomy: Rise of the Far-Right. World Policy

Journal. Accessed May 21, 2023. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26781463.

2014. Anti-immigrant Movement Links Immigration to

Terrorism. Anti-Defamation League. October 21. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.adl.org/resources/news/anti-immigrant-movement-links-immigration-terrorism.

Asbrink, Elisabeth. 2022. Sweden Is Becoming Unbearable.

The New York Times Company. September 20. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/20/opinion/sweden-democrats-elections.html.

Askew, Joshua. 2023. 'Keep Ireland Irish': Say hello to

Ireland's growing far right. Euronews. April 28. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.euronews.com/2023/03/13/keep-ireland-irish-say-hello-to-irelands-growing-far-right.

Balcells, Laia, and Gerard Torrats-Espinosa. 2018. Using

a natural experiment to estimate the electoral consequences of terrorist

attacks. Edited by James D. Fearon. Proceedings of the National Academy

of Sciences of the United States of America. October 2. Accessed May 21,

2023. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1800302115.

2022. Basic Principles. Isamaa Erakond. Accessed May

21, 2023. https://isamaa.ee/basic-principles/.

Beardsley, Eleanor. 2023. France's new far right.

NPR. January 16. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.npr.org/2023/01/16/1149425584/frances-new-far-right.

Bozóki, András. 2016. Mainstreaming the Far Right.

Presses Universitaires de France. December. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/27027095.

Bridge Initative Team. 2020. FACTSHEET: THE LEAGUE

(LEGA, LEGA NORD, THE NORTHERN LEAGUE). Georgetown University. September

14. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://bridge.georgetown.edu/research/factsheet-the-league-lega-lega-nord-the-northern-league/.

Cabral Fernandes, Ricardo. 2022. The Rise of Portugal’s

Far Right Is a Wake-Up Call. Jacobin. February 3. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://jacobin.com/2022/02/portugal-election-chega-far-right-andre-ventura.

Carls, Paul. 2021. Approaching right-wing populism in

the context of transnational economic integration: lessons from Luxembourg.

Informa UK Limited. October 28. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23745118.2021.1993056.

Chládková, Lucie. 2014. The Far Right in Slovenia.

Document. Edited by Miroslav Mareš. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of

Social Studies, Department of Political Science, May 10.

Chu, Leo. 2022. Latvian Parliamentary Elections: Party

Platform Guide. Foreign Policy Research Institute. September 28. Accessed

May 21, 2023.

https://www.fpri.org/article/2022/09/latvian-parliamentary-elections/.

Cimoszewicz, Włodzimierz. 2022. Opinion of the Committee

on Constitutional Affairs for the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and

Home Affairs on the proposal for a Council decision determining, pursuant to

Article 7(1) of the Treaty on European Union, the existence of a clear risk o.

Committee on Constitutional Affairs. May 19. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/AFCO-AD-729937_EN.pdf.

Conradt, David P. 2023. Green Party of Germany.

Edited by The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica.

May 14. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Green-Party-of-Germany.

Corder, Mike. 2023. Right-wing ‘folksy nationalism’

party wins in Dutch elections. The Christian Science Monitor. March 16.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2023/0316/Right-wing-folksy-nationalism-party-wins-in-Dutch-elections.

n.d. Croatia. European Commission. Accessed May 21,

2023. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/croatia_en.

n.d. Cyprus: Parties at a glance. PolitPro. Accessed

May 21, 2023. https://politpro.eu/en/cyprus/parties.

n.d. Czech Republic: Parties at a glance. PolitPro.

Accessed May 21, 2023. https://politpro.eu/en/czech-republic/parties.

Damhuis, Koen. 2019. “The biggest problem in the

Netherlands”: Understanding the Party for Freedom’s politicization of Islam.

Brookings. July 24. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-biggest-problem-in-the-netherlands-understanding-the-party-for-freedoms-politicization-of-islam/.

2023. Dansk Folkeparti - Denmark. Identity &

Democracy Group. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.idgroup.eu/dansk_folkeparti.

de Jonge, Léonie. 2021. The Rise and Fall of the Dutch

Forum for Democracy (FvD). European Consortium for Political Research.

September 3. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://ecpr.eu/Events/Event/PaperDetails/58970.

Doroshenko, Larisa. 2018. Far-Right Parties in the

European Union and Media Populism: A Comparative Analysis of 10 Countries

During European Parliament Elections. Edited by Larry Gross. University

of Southern California, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/7757/2422.

Dumitrescu, Radu. 2023. Supporters of Romanian far-right

party AUR turn violent during protest at Parliament. City Compass Media.

May 10. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.romania-insider.com/supporters-aur-turn-violent-during-protest-parliament-bucharest.

ECO News. 2018. Aliança: 13,000 signatures mark birth of

a new political party this Wednesday. Swipe News, SA. September 20.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://econews.pt/2018/09/20/alianca-13000-signatures-mark-birth-of-a-new-political-party-this-wednesday/.

Edo, Anthony, Yvonne Giesing, Jonathan Öztunc, and Panu

Poutvaara. 2019. Immigration and electoral support for the far-left and

the far-right. European Economic Review. June. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2019.03.001.

2019. ‘EU-27 and candidate countries’. European

Union. January 28. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://publications.europa.eu/code/pdf/370000en.htm.

2019. European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend

Report 2019. European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation. June

27. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/tesat_2019_final.pdf.

Fallon, Katy. 2019. Forum voor Democratie: Why has the

Dutch far right surged? Al Jazeera Media Network. March 25. Accessed May

21, 2023.

https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2019/3/25/forum-voor-democratie-why-has-the-dutch-far-right-surged.

2023. Finns Party. Wikimedia. April 13. Accessed May

21, 2023. https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q634277.

Fleck, Anna. 2022. How Much Sway Does the Far-Right

Have? September 26. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.statista.com/chart/6852/right-wing-populisms-enormous-potential-across-europe/.

Gallagher, Conor. 2023. Ireland First: Inside the group

chat of Ireland’s latest far-right political party. The Irish Times DAC.

March 12. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.irishtimes.com/ireland/social-affairs/2023/03/12/ireland-first-becomes-a-political-party-but-will-anyone-vote-for-it/.

Georgiadou, Vasiliki, Lamprini Rori, and Costas Roumanias.

2018. Mapping the European far right in the 21st century: A meso-level

analysis. Electoral Studies. August. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2018.05.004.

German Sirotnikova, Miroslava. 2021. Far-Right Extremism

in Slovakia: Hate, Guns, and Friends from Russia. BalkanInsight. January

20. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://balkaninsight.com/2021/01/20/far-right-extremism-in-slovakia/.

2023. Glossary:Country codes. Eurostat. January 16.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Country_codes.

Goerens, Annick. 2023. The ADR is not right-wing

extremist, says Fernand Kartheiser. RTL Luxembourg. February 1. Accessed

May 21, 2023. https://today.rtl.lu/news/luxembourg/a/2011579.html.

Golder, Matt. 2016. Far Right Parties in Europe.

May. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042814-012441#abstractSection.

Goncalves, Sergio, and Catarina Demony. 2023. Portugal

party Chega sets far-right world summit with Brazil's Bolsonaro, Italy's

Salvini. Edited by David Gregorio. Reuters. April 7. Accessed May 21,

2023.

https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/portugal-party-chega-sets-far-right-world-summit-with-brazils-bolsonaro-italys-2023-04-07/.

n.d. Google Translate. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://translate.google.com.

Gronholt-Pedersen, Jacob. 2021. Head of Denmark's

once-dominant far-right party steps down after election setback. Edited

by Nick Macfie and Angus MacSwan. Reuters. November 17. Accessed May 21,

2023.

https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/head-denmarks-once-dominant-far-right-party-steps-down-after-election-setback-2021-11-17/.

Hadjicostis, Menelaos. 2021. Far-right party, centrist

group gain big in Cyprus poll. The San Diego Union-Tribune. May 30.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/nation-world/story/2021-05-30/small-parties-look-to-gain-in-cyprus-parliamentary-vote.

Haughton, Tim, Marek Rybář, and Kevin Deegan-Krause. 2021. Leading

the Way, but Also Following the Trend: The Slovak National Party. Wayne

State University. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/honorssp/5/.

Helbling, Marc, and Daniel Meierrieks. 2020. Terrorism

and Migration: An Overview. British Journal of Political Science,

Cambridge University Press. December 17. Accessed May 21, 2023.

doi:10.1017/S0007123420000587.

Henley, Jon. 2023. Finland’s conservatives to open

coalition talks with far-right party. Guardian News & Media Limited.

April 27. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/27/finland-petteri-orpo-coalition-far-right-finns-party.

n.d. Hungary: Parties at a glance. PoliPro. Accessed

May 21, 2023. https://politpro.eu/en/hungary/parties.

2023. Immigration. Eurostat. October 29. Accessed

May 21, 2023.

https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/l0q3araj0g9dk3txzwkjg?locale=en.

n.d. Ireland: Parties at a glance. PoliPro. Accessed

May 21, 2023. https://politpro.eu/en/ireland/parties.

2023. Isamaa Parliamentary Group. April 13. Accessed

May 21, 2023.

https://www.riigikogu.ee/en/parliament-of-estonia/parliamentary-groups/isamaa-parliamentary-group/.

n.d. Italy: Parties at a glance. PolitPro. Accessed

May 21, 2023. https://politpro.eu/en/italy/parties.

2023. JA21 kicks of provincial campaign, aims for

pivotal role in senate. DutchNews. January 19. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.dutchnews.nl/2023/01/ja21-kicks-of-provincial-campaign-aims-for-pivotal-role-in-senate/.

Janos. 2022. The far right experience in Hungary.

Bureau of the Fourth International. June 5. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article7689.

Jegelevicius, Linas. 2023. Estonia's far-right EKRE

party should not be written off. bne IntelliNews Emerging Markets Direct

company. March 3. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://intellinews.com/estonia-s-far-right-ekre-party-should-not-be-written-off-271793/.

Jones, Sam. 2022. Spain’s far-right Vox breaks through

into regional government. Guardian News & Media Limited. March 10.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/10/spain-far-right-vox-regional-government-castilla-y-leon-peoples-party-deal.

Kessenich, Emma, and Wouter van der Brug. 2022. New

parties in a crowded electoral space: the (in)stability of radical right

voters in the Netherlands. National Library of Medicine, Nature

Publishing Group, Acta Polit. October 28. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9616406/.

Khalip, Andrei. 2011. PSD starts forming centre-right

Portuguese government. Reuters. June 5. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.reuters.com/article/cnews-us-portugal-election-idCATRE7532LZ20110606.

Kirby, Paul. 2022. Giorgia Meloni: Italy's far-right

wins election and vows to govern for all. BBC. September 26. Accessed May

21, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-63029909.

Kluonis, Mindaugas. 2020. Lithuania turns right:

urban-rural cleavage, generational change, and left-wing perspectives.

Foundation for European Progressive Studies. October 30. Accessed May 21,

2023.

https://progressivepost.eu/lithuania-turns-right-urban-rural-cleavage-generational-change-and-left-wing-perspectives/.

Kondor, Katherine. 2019. The Hungarian paradigm shift:

how right-wing are Fidesz supporters? openDemocracy. January 30. Accessed

May 21, 2023.

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/hungarian-paradigm-shift-how-right-wing-are-fidesz-supporters/.

Kulbaczewska-Figat, Małgorzata. 2020. The extreme right

in the Baltic States: Lithuania. Transform! European Network for

Alternative Thinking and Political Dialogue. June 9. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.transform-network.net/en/focus/overview/article/radical-far-and-populist-right/the-extreme-right-in-the-baltic-states-lithuania/.

Landsbergis, Gabrielius, and Linas Jegelevičius. 2019. Lithuanian

Conservatives’ tensions: can the party split? BNN.LV. August 15. Accessed

May 21, 2023.

https://bnn-news.com/lithuanian-conservatives-tensions-can-the-party-split-204320.

n.d. Latvia: Parties at a glance. PolitPro. Accessed

May 21, 2023. https://politpro.eu/en/latvia/parties.

Le Monde, AFP. 2022. Sweden's right-wing announces new

government with far-right backing. October 14. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.lemonde.fr/en/europe/article/2022/10/14/sweden-s-right-wing-announces-new-government-with-far-right-backing_6000299_143.html.

2023. Lega Nord. Counter Extremism Project. Accessed

May 21, 2023. https://www.counterextremism.com/supremacy/lega-nord.

n.d. Lithuania: Parties at a glance. PolitPro.

Accessed May 21, 2023. https://politpro.eu/en/lithuania/parties.

Lonsky, Jakub. 2020. Does immigration decrease far-right

popularity? Evidence from Finnish municipalities. Edited by Klaus F.

Zimmermann and Madeline Zavodny. Journal of Population Economics. July 7.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148-020-00784-4.

Mac Dougall, David. 2023. Estonia election analysis: Why

the liberals won, the far-right lost, and other key takeaways. Euronews.

August 3. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.euronews.com/2023/03/06/estonia-election-analysis-why-the-liberals-won-the-far-right-lost-and-other-key-takeaways.

Markou, Grigoris. 2021. The systemic metamorphosis of

Greece’s once radical left-wing SYRIZA party. openDemocracy. June 14.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/rethinking-populism/the-systemic-metamorphosis-of-greeces-once-radical-left-wing-syriza-party/.

McGrath, Stephen. 2020. How a far-right party came from

nowhere to stun Romania in Sunday's election. Euronews. August 12.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2020/12/08/how-a-far-right-party-came-from-nowhere-to-stun-romania-in-sunday-s-election.

Misiunas, Romuald J. 1970. Fascist Tendencies in

Lithuania. Modern Humanities Research Association and University College

London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4206165.

2018. Movement for Social Democracy party (EDEK,

Cyprus). Clean Energy Wire. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.cleanenergywire.org/experts/movement-social-democracy-party-edek-cyprus.

Mudde, Cas. 2019. The 2019 EU Elections: Moving the

Center. Journal of Democracy. October. Accessed May 21, 2023.

doi:10.1353/jod.2019.0066.

—. 2014. The far right in the 2014 European elections:

Of earthquakes, cartels and designer fascists. The Washington Post. May

30. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2014/05/30/the-far-right-in-the-2014-european-elections-of-earthquakes-cartels-and-designer-fascists/.

Muller, Robert, and Jan Lopatka. 2017. Far-right scores

surprise success in Czech election. Reuters. October 21. Accessed May 21,

2023.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-czech-election-farright/far-right-scores-surprise-success-in-czech-election-idUSKBN1CQ0T3.

Nellas, Demetris. 2014. Greece's Neo-Nazi Party May Be

Forced To Change Its Name. Insider Inc. February 4. Accessed May 21,

2023. https://www.businessinsider.com/golden-dawn-name-change-2014-2.

n.d. Netherlands: Parties at a glance. PolitPro.

Accessed May 21, 2023. https://politpro.eu/en/netherlands/parties.

2011. People of Freedom (Il Popolo della Liberta, PdL).

John Pike. November 7. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/europe/it-political-parties-pdl.htm.

Petsinis, Vassilis. 2019. Identity Politics and

Right-Wing Populism in Estonia: The Case of EKRE. Informa UK Limited.

June 21. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13537113.2019.1602374?journalCode=fnep20.

Piccolino, Gianluca, and Leonardo Puelo. 2022. Between

far-right politics and pragmatism: Assessing Fratelli d’Italia’s policy

agenda. The London School of Economics and Political Science. October 6.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2022/10/06/between-far-right-politics-and-pragmatism-assessing-fratelli-ditalias-policy-agenda/.

n.d. Poland: Parties at a glance. PolitPro. Accessed

May 21, 2023. https://politpro.eu/en/poland/parties.

n.d. Portugal: Parties at a glance. PolitPro.

Accessed May 21, 2023. https://politpro.eu/en/portugal/parties.

2021. Publications. European Union Agency for Law

Enforcement Cooperation. November 25. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-events/publications?q=te-sat.

2017. Radical Right-Wing Political Parties and Groups.

NBS-Media. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://civic-nation.org/romania/society/radical_right-wing_political_parties_and_groups/.

2017. Radical Right-Wing Political Parties and Groups.

NBS-Media. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://civic-nation.org/ireland/society/radical_right-wing_political_parties_and_groups/.

2017. Radical Right-Wing Political Parties and Groups.

NBS-Media. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://civic-nation.org/bulgaria/society/radical_right-wing_political_parties_and_groups/.

2017. Radical Right-Wing Political Parties and Groups.

NBS-Media. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://civic-nation.org/croatia/society/radical_right-wing_political_parties_and_groups/.

2017. Radical Right-Wing Political Parties and Groups.

NBS-Media. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://civic-nation.org/finland/society/radical_right-wing_political_parties_and_groups/.

Rankin, Jennifer. 2022. Pro-EU politicians hail defeat

of Slovenia’s hard-right prime minister. Guardian News & Media

Limited. April 25. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/25/pro-eu-politicians-herald-defeat-slovenia-hard-right-janez-jansa-robert-golob.

Ray, Michael. 2023. National Rally. Edited by The

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica. May 4. Accessed

May 21, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/National-Rally-France.

Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board,

Canada. 1999. Romania: The activities of the Greater Romania Party, and

their position towards Roma (January 1998 - July 1999). United Nations

High Commissioner for Refugees. July 1. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6ab3090.html.

Romania Insider. 2019. Romania presidential elections

2019: Who is Mircea Diaconu, the actor who wants to be the first independent

president? City Compass Media. November 7. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.romania-insider.com/romania-presidential-elections-2019-mircea-diaconu.

Rorke, Bernard. 2010. The Rise of the Far Right and

Anti-Gypsyism in Hungary. Open Society Foundations. April 12. Accessed

May 21, 2023.

https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/rise-far-right-and-anti-gypsyism-hungary.

RTL. 2023. Is there a far right in Luxembourg? RTL

Luxembourg. March 2. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://today.rtl.lu/news/luxembourg/a/2042943.html.

Schumacher, Elizabeth. 2018. Matteo Salvini: Italy's

far-right success story. Deutsche Welle. March 5. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.dw.com/en/matteo-salvini-italys-far-right-success-story/a-42830366.

Share, Donald. 2023. Popular Party. Edited by The

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. March 22. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Popular-Party-Spain.

Simeonova, Elitsa, and Tony Wesolowsky. 2022. Revival On

The Rise: Ahead Of Elections, Far-Right Party Is Tapping Into Bulgarian

Public Anger. RFE/RL, Inc. October 1. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.rferl.org/a/bulgaria-elections-revival-pro-russian/32060748.html.

Smith, Helena. 2021. Cyprus election: far-right party

linked to Greek neo-Nazis doubles vote share. Guardian News & Media

Limited. May 30. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/30/far-right-cyprus-election-parliament.

Smolík, Josef. 2011. Far right-wing political parties

in the Czech Republic: heterogeneity, cooperation, competition. Accessed

May 21, 2023. https://sjps.fsvucm.sk/Articles/11_2_1.pdf.

n.d. Spain: Parties at a glance. Accessed May 21,

2023. https://politpro.eu/en/spain/parties.

Stamouli, Nektaria. 2023. Greek parliament votes to ban

extreme-right party from elections. Politico. April 11. Accessed May 21,

2023.

https://www.politico.eu/article/greece-votes-outlaw-extreme-right-party-from-elections/.

Terenzani, Michaela, and Roman Cuprik. 2022. Slovakia's

Far-Right L'SNS Party: Saved by Its Perceived Irrelevance.

BalkanInslight. August 24. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://balkaninsight.com/2022/08/24/slovakias-far-right-lsns-party-saved-by-its-perceived-irrelevance/.

2011. The state of the right : the Netherlands.

Fondation pour L'innovation Politique. March. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.fondapol.org/en/study/the-state-of-the-right-the-netherlands/.

Tilles, Daniel. 2023. Polish far right eyes role as

kingmaker after this year’s elections. Notes from Poland. April 2.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://notesfrompoland.com/2023/04/02/polish-far-right-eyes-role-as-kingmaker-after-this-years-elections/.

2023. Totul Pentru Tara. EHRI Consortium. Accessed

May 21, 2023. https://portal.ehri-project.eu/authorities/ehri_cb-1029.

Tremlett, Giles. 2009. Conservatives woo far right ally

in Spain. Guardian News & Media Limited. May 29. Accessed May 21,

2023.

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2009/may/29/conservatives-ally-far-right-party-spain-european-elections.

Trilling, Daniel. 2020. Golden Dawn: the rise and fall

of Greece’s neo-Nazis. Guardian News & Media Limited. March 3.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2020/mar/03/golden-dawn-the-rise-and-fall-of-greece-neo-nazi-trial.

Vejvodová, Petra, Jakub Janda, and Veronika Víchová.

2017. The Russian connections of far-right and paramilitary organizations

in the Czech Republic. Edited by Edit Zgut and Lóránt Győri. Political

Capital. April. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://politicalcapital.hu/pc-admin/source/documents/PC_NED_country_study_CZ_20170428.pdf.

n.d. Welcome. EuropäischeLINKE. Accessed May 21,

2023. https://en.die-linke.de/welcome/.

Wike, Richard, Jacob Poushter, Lauren Silver, Kat Devlin,

Janell Fetterolf, Alexandra Castillo, and Christine Huang. 2019. Views on

the European Union across Europe. Pew Research Center. October 14.

Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/10/14/the-european-union/.

Wike, Richard, Janell Fetterolf, and Moira Fagan. 2019. Europeans

Credit EU With Promoting Peace and Prosperity, but Say Brussels Is Out of

Touch With Its Citizens. Pew Research Center. March 19. Accessed May 21,

2023.

https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/03/19/europeans-credit-eu-with-promoting-peace-and-prosperity-but-say-brussels-is-out-of-touch-with-its-citizens/.

Witting, Volker. 2023. Germany's far-right AfD marks 10

years since its founding. Deutsche Welle. February 5. Accessed May 21,

2023.

https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-far-right-afd-marks-10-years-since-its-founding/a-64607308.

Zay, Éva. 2020. A new Transylvanian Hungarian party in

the works. Transylvania Now. January 20. Accessed May 21, 2023.

https://transylvanianow.com/a-new-transylvanian-hungarian-party-in-the-works/.